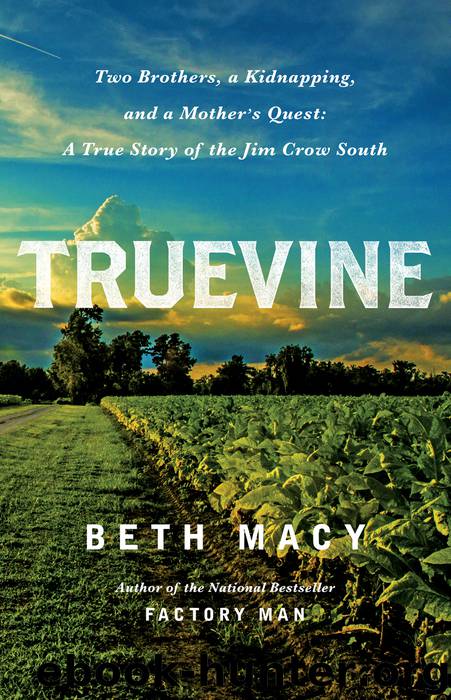

Truevine by Beth Macy

Author:Beth Macy

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History / United States / 20th Century, History / United States / General, Biography & Autobiography / Cultural Heritage, Biography & Autobiography / Historical

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Published: 2016-10-17T16:00:00+00:00

11

Adultery’s Siamese Twin

The money—first from the change cup on the porch, then from the Ringling settlement and the funds being sent home—changed everything at Ten-and-a-Half Street. The food went from pinto beans to steak. The nip-joint shot glasses turned into whiskey in a jar—bought by the case.

The black-owned Baltimore Afro-American painted the metamorphosis of Cabell Muse in a disapproving glare. The paper said he had long been “feared by men of lower strata,” a well-known bully in the black community.

But now, emboldened by the sudden infusion of settlement cash, he was becoming even more “overbearing and brutish in his associations.” He hogged the Muse brothers’ back pay for himself, spending it on a brand-new car and other luxuries. Harriett’s dream of buying property would have to wait.

For a young A. L. Holland, the behavior of Cabell Muse became a morality lesson that underscored his own father’s sense of duty: instead of blowing money on a car, Gus Holland walked to his rail-yard job and squirreled away his earnings, giving him something that would buttress the family for generations rather than bleed it dry—home ownership.

The Hollands wasted little money buying food because they kept chickens in the backyard for eggs, and they canned vegetables they grew in the yard. Instead of buying coal to heat their stoves, Gus Holland carted home leftover cross ties from work, using the scrap wood for free fuel. The children, who grew up chopping kindling for the stove every night before they went to bed, would adopt a metaphor for their father’s lessons: “We made cotton, but we took that cotton and made silk.”

Cabell was definitely the only blue-collar worker in town with the fortune—and the audacity—to buy a car. To a person, blue-collar African Americans in Roanoke aspiring to join the middle class in the late 1920s “walked to work. Didn’t nobody have a car,” Holland recalled. “I mean, Dr. Pinkard and Dr. Claytor and maybe the lawyer had a car.”

Holland didn’t recall what brand Cabell’s car was (nor did anyone in the family), just that “it was real nice.” Buick models introduced in 1928, at the peak of the stock market bubble, ranged from $1,195 to $1,850, around the average American’s annual salary.

Back then, the speed limit outside city limits was forty-five miles per hour. A trip from Roanoke to Charlottesville that now takes two hours by way of the four-lane interstate then took eleven. Roads were twisty and riddled with potholes. The Roanoke Times was filled with morbid accounts of cars careening off mountainsides and ramming into each other. In one instance, a Rocky Mount man was repairing a blown-out tire on the roadside in the fall of 1927 when a speeding motorist slammed into him, breaking most of his bones, then drove away. The injured man died the next day.

Henry Ford’s mass-production methods already had transformed the way Americans worked, played, and spent their money. The car became the status symbol for aspirational Americans. If you owned a car, it meant you

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Asia |

| Canadian | Europe |

| Holocaust | Latin America |

| Middle East | United States |

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26579)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23055)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16837)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13279)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(7098)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5482)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5069)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4782)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4782)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4440)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4333)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4235)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4166)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4076)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4009)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3936)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3620)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3449)